Joan Fontcuberta: false negatives

In 1968, during a routine space walk, the Russian cosmonaut Ivan Istochnikov and his dog went missing. When Soyuz 3 was dispatched to find them, its crew found only a vodka bottle containing a note, floating outside the empty, meteorite-damaged ship.

Nothing was heard about Istochnikov for nearly three decades: it was as though the Soviet authorities had airbrushed their cosmonaut from history. Then, in 1997, Catalan photographer Joan Fontcubertainvestigated Istochnikov's disappearance, exhibited documentary evidence about his life and published a book called Sputnik – the Odyssey of the Soyuz II, which included photographs of the Istochinikov family, meteorite fragments and the dented spacecraft. Others took up the story. Why, asked Spanish journalist Iker Jiménez on his TV show Cuarto Milenio in 2006, was Istochnikov deleted from history? Had he annoyed the Soviet government?

What Jiménez didn't realise is that "Ivan Istochnikov" is a Russian translation of "Joan Fontcuberta" (both surnames mean hidden fountain). What's more, if he'd looked closer at the Istochnikov family photos he would have noticed that the Russian cosmonaut was really a Catalan photographer. The whole thing was a hoax, elaborately documented by an artist ("I prefer to think of myself as an activist," Fontcuberta corrects me when we meet) to expose the construction of reality masked by the putatively neutral nature of documentaryphotography. There was no meteorite, no cosmonaut, no conspiracy, and – happily – no dead dog drifting eternally in space like a canine George Clooney.

Why would you devise such an elaborate hoax, I ask Fontcuberta in a hotel bar, ahead of his first major UK show, at London's Science Museum and then Bradford's National Media Museum? "My model is Jorge Luis Borges [the Argentine writer behind many literary hoaxes]. The idea is to challenge disciplines that claim authority to represent the real – botany, topology, any scientific discourse, the media, even religion.I chose photography because it was a metaphor of power. When I started in the early 70s, photography was a charismatic medium providing evidence."

But some don't like this challenge to authority, still less being teased by an artist who deploys the reality-subverting techniques of Catalan artistic predecessors (Fontcuberta cites Dalí and Miró). A Russian ambassador apparently threatened a diplomatic complaint because Fontcuberta had insulted "the glorious Russian past".

Fontcuberta and I giggle over this story, but then I wonder. Perhaps there was no credulous journalist called Iker Jiménez, no stereotypically angry Russian ambassador. Maybe these characters were invented as part of a more elaborate hoax that Fontcuberta inserted into his Wikipedia page and online interviews to make a monkey of the Guardian's interviewer. I glance sidelong at the genial 59-year-old as he takes a swig of beer: I wouldn't put it past him.

Fontcuberta has made a career out of such hoaxes. In 2000, for instance, he installed mermaid fossils in rocks at the Réserve Géologique de Haute-Provence in southern France. He created an allied exhibition about the fossils, complete with photographic documentary evidence about a Father Jean Fontana who had discovered these "Hydropithecus" (water-monkey) fossils. In the photos, the French priest looked, as you might have guessed, more than a little like Fontcuberta.

Soon after this artistic intervention, Sirens, became public, Fontcuberta received angry letters from schoolteachers. "They said it's very difficult to teach our kids how evolution works when you're amending the fossil record." But, Fontcuberta maintains, his hoax had a serious point. "To me, Sirens is a tool that teaches us to explain evolution. They saw my work as a danger, probably because they are intellectually lazy, but if they were intellectually engaged they could push their students to understand how we construct models to understand reality."

With Sirens and his other works in the new show, Fontcuberta hopes to do more than submit visitors to practical jokes. "My work – I wouldn't want to be pretentious – is pedagogic. It's a pedagogy of doubt, protecting us from the disease of manipulation. We want to believe. Believing is more comfortable because unbelieving implies effort, confrontation. We passively receive a lot of information from TV, the media and the internet because we are reluctant to expend the energy needed to be skeptical."

To visit the Fontcuberta exhibition at the Science Museum requires the rewarding expenditure of much critical energy. Once you've exposed the hoax to your own satisfaction, another question opens up: why should you trust the bona fides of anything you see, even if it comes with theimprimatur of a respectable museum?

In another of his projects, Fauna,for instance, Fontcuberta and a collaborator with the suspicious-sounding name Pere Formiguera claimed to have rediscovered the long-lost archives of German zoologist Dr Peter Ameisenhaufen, who disappeared mysteriously in 1955. Before his disappearance, Ameisenhaufen had catalogued a number of unusual animals, including "Ceropithecus icarocornu", a monkey with wings and a unicorn-like horn, and "Solenoglypha polipodida", which resembles a snake but with 12 feet. "I present the whole story in a detailed museological display, which means I have vitrines, stuffed animals, bird-song recordings, x-rays, photographs, field sketches – everything you expect from a natural-history display."

But, I ask, steeling myself for disappointment, are there really no flying monkeys? "Of course not," says Fontcuberta. We rely on museums not to Photoshop wings and horns on monkeys and pass them off as interesting mutations. But if they did, Fontcuberta contends, such is their authority that we might suspend our critical faculties.

Indeed, when Fauna was shown at the Barcelona Museum of Natural Science in 1989, 30% of university-educated visitors aged 20 to 30 believed some of the imaginary animals Fontcuberta devised could have existed.

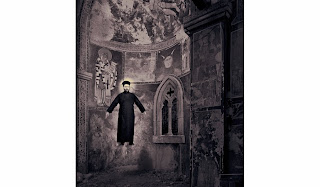

Elsewhere in Stranger than Fiction, visitors will see Constellations (1993), purportedly photographs of magnificent starry skies but in reality photograms made using the dust from a car windscreen, and Orogenesis (2002), a series of landscapes brought to life by Fontcuberta feeding misinformation into cartographical software normally used by geographers and the military. Karelia: Miracles and Co (2002) documents Fontcuberta's story about a trip he undertook, posing as a monk, to expose the truth of a Finnish monastery where it is said that monks learn how to perform miracles. Truly you will believe, having seen the evidence, that a monk (looking uncannily like a certain Catalan photographer) can walk on water.

"I'm a terrible photographer," Fontcuberta says. Why? By way of answer he shows me his hand – there is a finger missing. "A homemade bomb blew up in my hand, so I'm very slow in using a camera." So what, I say: Django Reinhardt lost a couple of his fingers but that didn't stop him being a great guitarist. Perhaps it helped. "I tried to work as a documentary photographer but I was a bullshitter. So I thought I should work on the other side." (For a "terrible" photographer, he is a successful one: last year he won the Hasselblad International Award in Photography, whose previous recipients include Ansel Adams and Henri Cartier-Bresson.)

One reason that questioning authority became part of Fontcuberta's vocation is Spain's fascist ruler, General Franco. "I lived for 20 years under the Francoist regime, so like all my generation I suffered from the lack of transparency and the doctoring of documents to reconstruct history."

Fontcuberta has a degree in communications and previously worked in advertising. As well as making his art, he now teaches all over the world. "I'm an heir of Marshall McLuhan [the Canadian media theorist who counseled that the medium is the message] and of all those 1960s countercultural movements – situationism, conceptual art. Mix them all in a cocktail and that's me."

Some photographers wouldn't deign to sip this heady cocktail. "That's right. For them photography is neutral. But really, as Walter Benjamin recognised, it's a medium impregnated with all the ideological values of the 19th century – the industrial revolution, liberalism, colonialism, positivism, realism. When you push the button of a camera all that is compressed. As a photographer, you must be aware of that heritage.

"You see," says Fontcuberta just before we finish our drinks, "reality doesn't exist before our experience. Photography is one of the tools that helps us construct reality. It is not an innocent medium."

• Stranger than Fiction is at the Science Museum, London SW7, 23 July–9 November; and National Media Museum, Bradford, 19 November–8 February 2015

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jul/08/joan-fontcuberta-stranger-than-fiction#

Comentarios